Empathy makes you better at fighting misinformation, here's how

We need to talk about how we talk about "conspiracy theorists"

A Deeper Truths reader left a comment on my recent piece about the 20mph culture war and ‘Super Distrusters’ which stayed with me. It raises the question of empathy, and its role in our thinking as communicators engaging with sceptics and distrusters:

“I think it would also be helpful to reflect on why people become ‘distrusters’ - in some cases years of being on the wrong end of difficult decisions and not being listened to?”

And it’s true. I can hold my hands up and say I’ve been guilty of this: in my natural defensiveness to untrue information about my work, I’ve spoken about those spreading misinformation in reductive and unhelpful terms. It feels therapeutic, but this mindset (I’m going to argue) makes us worse at our jobs.

Stay with me. This might not seem like practical advice, but I’m going to make a four-part case here for why empathy can make us better at fighting misinformation.

Empathy can maintain morale

“Being too cynical and pleasantly surprised is not more sophisticated than being too idealistic and disappointed.” - Jon Lovett, political strategist

In my experience, the first mistake we make as communicators when we’re faced with a misinformation challenge, is that we assume the problem is all external.

This is an attractive lens through which to view the problem. External problems can be quantified and measured. Internal problems are messy and require self-reflection. And yet often the real damage caused by misinformation is the downward spiral which is fuelled by our internal, and very human, ‘feelings’.

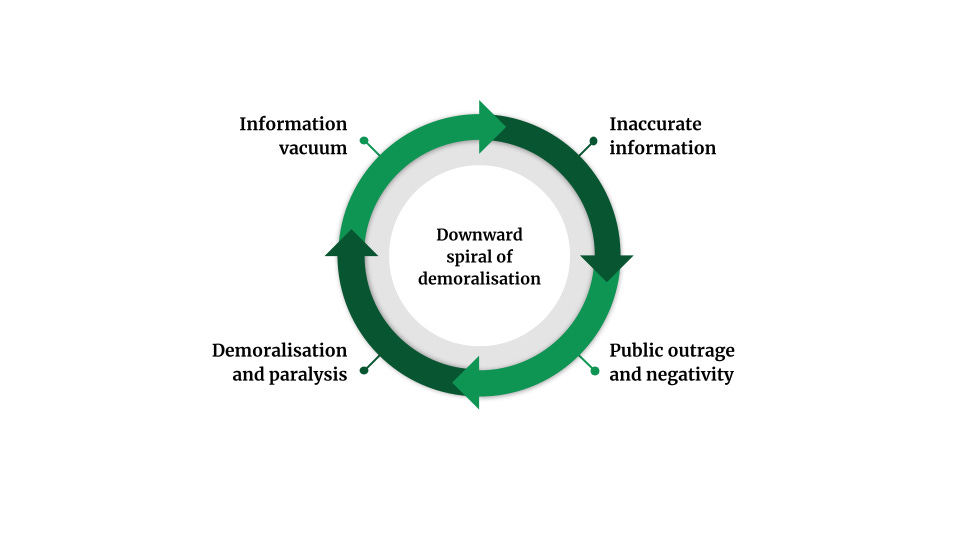

The cycle looks something like this:

Misinformation doesn’t just give people the wrong information and cause harmful behaviours, it distracts us from our core message and drains our creative morale and energy.

The first piece of advice I give to organisations I work with is keep going. If we have a simple and coherent message, the worst thing we can do is stop using it every time we feel the heat of public outrage. Yet this paralysis is a normal reaction to the online noise. After all, why would we want to give more fuel to our ‘adversaries’?

But when we consider the following questions, we may begin to find our resolve again:

What if, instead of seeing it through an adversarial lens, we took the time to think about those who are being misled by the bad information? What negative impact is this having on their lives?

What if we zoomed out from the toxicity of social media and considered the broader complexities and stresses of the lives of those spreading misinformation? What else is going on here?

What if we thought about all of the reasonable people beyond the noise of social media who desperately need access to high quality information?

I’ve found through personal experience, that bringing myself back to these questions helps me stay focused and energised.

(Caveat: This obviously does not extend to those being hateful and abusive online. In this case, make use of the two Bs: Block and take a Break.)

Empathy stops us alienating people

The research on those prone to believing in conspiracy theories and misinformation shows that these types of misleading narratives fulfil the following human needs:

Our need to understand the world around us

Our need to feel safe and in control over our lives

Our need to maintain our self-image as a good person and be part of a community which is making the world better

It won’t have escaped your notice that our increasingly complex, crisis-ridden and at times atomised world probably isn’t helping. However, if we start from a place of ‘othering’ — demonising or ridiculing those who are falling for the bad information — we’re more likely to engage in actions that further alienate them, pushing them towards misinformed stories which fulfil these human needs.

If people feel like we’re questioning their moral integrity or intelligence, they’re more likely to reject anything we have to say. If we can communicate with these audiences in a way that helps them make sense of the world around them, gives them control and autonomy, and doesn’t threaten their sense of self-image — then we’re much more likely to be heard.

Empathy creates better conversations

Sometimes our conversations with ‘Super Distrusters’ won’t be online, they’ll be in person. How do we utilise empathy in these conversations to make sure that our message lands and the person on the receiving end feels heard too?

Starting with empathy can make sure these conversations are set up to succeed, but this can be bolstered with concrete conversational approaches that help us put this feeling into action. The science of effective conversations around behaviour change comes from the field of Motivational Interviewing (MI), and the most relevant components in this context include:

A non-judgemental approach, where the ‘practitioner’ (you) engages as a compassionate partner (not an adversary), drawing out the person’s own priorities and values — not imprinting your own.

A series of techniques designed to facilitate this respectful exchange, including:

Open questions (“Why are policies like this one so important to you?”)

Affirmations (“You care a lot about your community, and you want to see that politicians do too”)

Reflective listening, which draws attention to more constructive statements (“You feel like you’ve been let down by politicians, and yet you understand the importance of road safety”)

Consensual exchange of information (“Would you be open to me sharing with you some information about the impact that 20mph speed limits have had elsewhere?”)

If you’re interested in how MI is relevant in a more political context, then Deep Canvassing is a good place to start.

Maybe they’re (kind of) right? Empathy helps us address root causes

The best thing our political leaders can do to tackle the damage caused by misinformation (apart from spreading it themselves) is to tackle inequality.

I’ll revisit this subject in future emails, but in a LinkedIn post from earlier this year I made the argument that many of the countries we consider to be ‘beating’ misinformation with public education, also happen to be prosperous societies with high standards of living and low levels of inequality.

It should be no surprise that we find challenges with misinformation and polarisation where we have unequal societies. These narratives are fuelled by mistrust of elites, and so they’re more likely to appear where political elites have failed to provide adequate living standards for their citizens.

You may feel as though public outrage at your work is based on a foundation of incorrect information. Yet when you see things from ‘their’ perspective, it might be reasonable to wonder why, for example, in the context of declining living standards, rising bills and limited access to public transport, they are being asked to pay extra to drive their cars through their home town. Why are billionaires not being taxed more for their private jets?

These might not be questions you can answer, but like it or not, they impact your ability to communicate your work. The ‘misinformation’ isn’t driving the opinions here, it’s merely a vehicle for the emotion. Understanding the emotional context of your audiences helps you understand the difficulty of the information environment.

What else?

Have you succumbed to the spiral of demoralisation in your work? How has it impacted you and how did you get out of it? Have you made use of empathy in your own work?

Or maybe you reject the assumptions of my argument? Even better! Write back and let me know.

Would you like to know more about how you can limit the impacts of misinformation on your work? Take a look at my website and inquire about my services.